Trump Must Learn from Machiavelli

Editor's Note

Immigration enforcement has become the decisive measure of American sovereignty because it tests whether the state retains the capacity to distinguish between citizen and non-citizen and to act upon that distinction. Resistance to deportation is no longer episodic or peripheral; it reflects a widening refusal, by organized actors and sympathetic institutions, to acknowledge the authority of law when it collides with ideological commitment.

In this essay, Glenn Ellmers situates President Trump’s predicament within the tradition of political realism, where moments of regime stress reveal the fragility of moral restraint. Machiavelli, Nietzsche, and Strauss provide the conceptual vocabulary for examining a recurring problem in republican government: the point at which moderation ceases to preserve order and begins to undermine it. The question Ellmers presents is whether a constitutional polity can endure when its defenders remain bound by scruples that their adversaries have long since discarded.

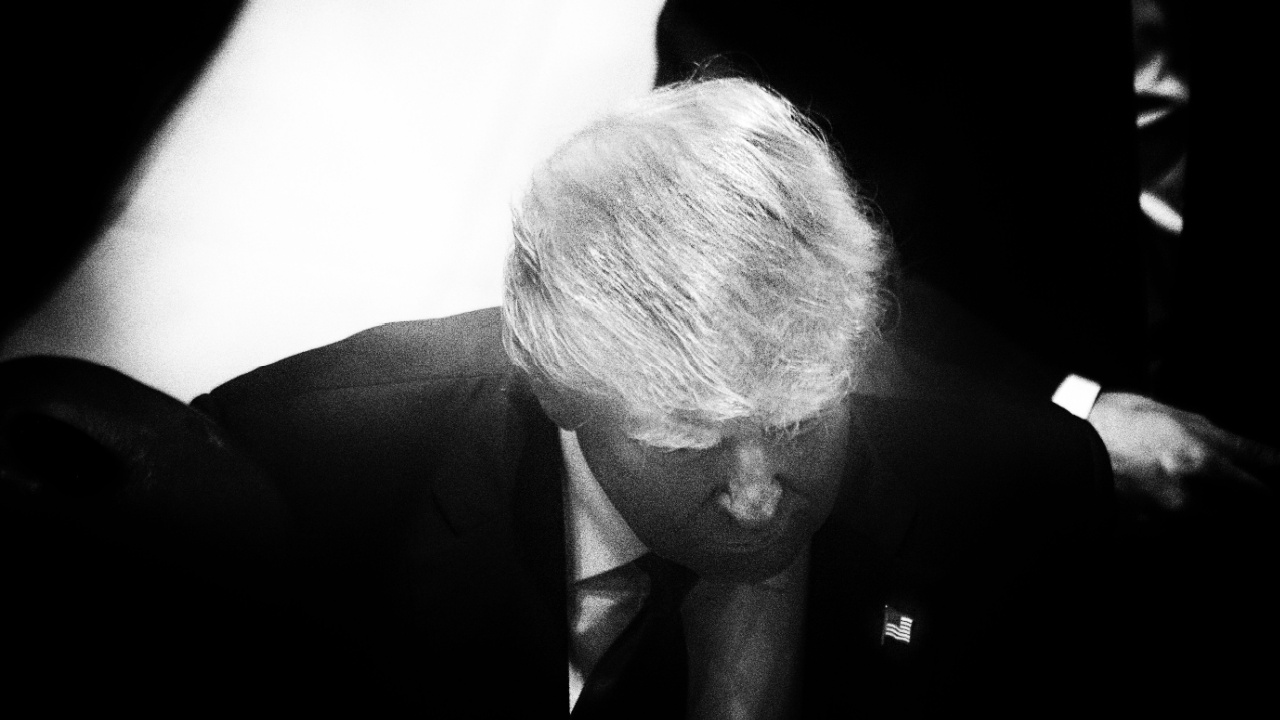

One year into his second term, President Trump has achieved a great deal, but his situation is more precarious than it has ever been.

Under the Biden administration, the Democrats illegally imported 10 million new voters. Those votes will be essential if the deep state is to succeed in defeating MAGA and restoring the old uniparty establishment. The Left isn’t going to give up its army of foreign supporters without a fight. So the fight is on.

The massive resistance to ICE’s enforcement of our immigration laws captures almost every major controversy facing the United States today. The massive Somali welfare fraud in Minnesota, Maine, and elsewhere; DEI propaganda; globalism; even Nicolás Maduro’s narco-terrorism — all of these turn on the question of whether the U.S. can control its own borders and its own destiny. What hangs in the balance is not merely party registrations and election results — although those are critically important. This battle will determine the meaning of American citizenship and whether or not the United States remains a sovereign nation.

The anti-deportation protests comprise two very different elements: paid militants and deluded idealists — the latter including a disproportionate number of suburban white women. What drives these well-educated, relatively affluent wives and mothers to defend even the worst among the illegal aliens, including lethal drunk drivers, child abusers, and sex traffickers? The answer shows that we are long past ordinary partisan differences; this is a civilizational crisis. Friedrich Nietzsche anticipated this phenomenon more than a century ago. In Beyond Good and Evil, he writes:

There is a point in the history of society when it becomes so pathologically soft and tender that among other things it sides even with those who harm it, criminals, and does this quite seriously and honestly. Punishing somehow seems unfair to it, and it is certain that imagining “punishment” and “being supposed to punish” hurts it, arouses fear in it. “Is it not enough to render him undangerous? Why still punish? Punishing itself is terrible.” With this question, herd morality, the morality of timidity, draws its ultimate consequence.

This suicidal empathy would be dangerous enough on its own, but the Left has brilliantly weaponized the neuroses of liberal white women through the “force multiplier” of hired hooligans. We are only beginning to discover the vast scope of this domestic terrorism network, which involves tens of thousands of people working to subvert the Constitution. A fifth column of professional anarcho-communists, trained and willing to engage in violence, can be mobilized to appear in any American city on a day’s notice. It is probably larger, better funded, and better organized than the Soviet Union’s spy network in the U.S. at the height of the Cold War.

This puts Trump in a tight spot. Nietzsche’s great teacher, Niccolò Machiavelli—who more than any other figure in history investigated political extremism, and showed what extreme circumstances demand—would sympathize with Trump’s predicament. The pathological softness that Nietzsche describes was already evident to Machiavelli in sixteenth century Florence. His whole project, in fact, was to overcome what he regarded as the feckless timidity engendered by modern delicate sensibilities. Machiavelli would also have some advice for Trump, but whether the president (or any American) would be willing to accept that advice is another matter.

From Machiavelli’s perspective, Trump is courting catastrophe by trying to steer an impossible middle course—a common error for most politicians. Trump has excited and animated his enemies without making them fear him. Machiavelli would say that this error comes from trying to be bold, but not being bold enough. Trump’s enemies call him a fascist and deride ICE agents as Gestapo troops, knowing that this charge is entirely performative. Confronted with real SS stormtroopers, the ridiculous wine moms in Minneapolis would fall into a dead faint, or flee in terror. No German citizen in the 1930s and ’40s ever dared to spit in the face of a Gestapo officer, or run one over with her car. The result, as everyone knew, would have been an agonizing death by torture.

Trump recognizes that the country is facing a critical inflection point: if we don’t deport Biden’s army of invaders now, we never will. Trump sees this; yet his attachment to the ordinary expectations of republican principles and the rule of law restrains him from doing what is required. He is unwilling to be what Machiavelli called “wholly bad.” It “very rarely happens,” the Florentine tells us, that a bad man will use his power for good ends. But it is just as rare for a good man to embrace “bad ways, even though his end be good.”

The brilliant professor of political philosophy Leo Strauss, in his book on Machiavelli, examines the difficulty confronting a political leader whose moral conscience holds him back from terrible, but necessary, actions. This “failure of courage,” Strauss explains, can be hard to understand. Often, such leaders “do not know what stopped them; for what stopped them was an uncanny mixture of power and graciousness. One cannot say that the failure was due either to lack of courage or to lack of prudence but one can say definitely that it was due to ‘a confusion of the brain.’”

Of course, it is possible Trump is not confused at all. It is hard to know what he is thinking, in part because he is naturally unpredictable, but also because he is keeping his cards much closer to his vest in his second term. He’s learned that there are few people he can trust. What is obvious, however, is that Trump has to take great risks to save the country. We live in dangerous times; it is impossible to avoid dangerous measures. What remains to be seen is how extreme Trump is willing to be.

Machiavellian realism would force us to confront the paradoxical possibility that the American republic can only be saved by a leader willing to be wholly bad in the service of an aim that is wholly good. Trump is too American to be fully Machiavellian. This very limitation may prevent him from doing what it takes to win the war for America’s soul. If Trump ultimately fails, it will be because he refuses to be as wicked as his enemies already believe him to be. Machiavelli would not be surprised. Our situation is the clearest confirmation in my lifetime of the truth and moderation of the controversial maxim written by Harry Jaffa 60 years ago: “extremism in the defense of liberty is no vice.”