Power Without Responsibility

Editor’s Note: The first step in winning a war is to recognize the fact that you are in one. This means, first and foremost, to come to know your enemy and his goals. In a recent essay for this site, Glenn Ellmers and Ted Richards of the Claremont Institute make a compelling case that the present enemy—the “woke” or group quota regime—is a totalitarian threat, and that its aims are nothing short of revolutionary. While our own troubles may seem far removed from the hard totalitarianism of the twentieth century, Ellmers and Richards argue that the six traditionally accepted elements of totalitarianism are already present in woke America. What’s more, they identify three factors that are unique to the tyranny of the present day.

In the 20th century, totalitarianism was marked by the rule of strongmen, from Hitler and Mussolini to Stalin, Mao, and beyond. Now, argues Helen Andrews, a totalitarianism is emerging whose rulers cannot be named, much less confronted—making this new regime all the more dangerous. This is the sixth in a series of nine contributions by leading experts on the nine defining elements of what Ellmers and Richards dub “Totalitarianism, American Style.”

The literature on “totalitarianism” was a product of the Cold War. What made us better than the Soviets? That was easy to answer when Stalin was in power. They feared the midnight knock on the door; we didn’t. But as the 1950s wore on and the Soviet system moderated, it became easier for left-wing Americans to draw equivalences. The South’s oppression of blacks, McCarthyite paranoia, suburban conformity—perhaps we were no more free than the Russians?

In order to answer these arguments, political scientists developed checklists. One such was Zbigniew Brzezinski and Carl Friedrich’s in 1956, to which Gabriel Schoenfeld appeals in the article to which Glenn Ellmers and Ted Richards respond in their essay “Totalitarianism, American Style.” There were other checklists by other scholars. All of them aimed to define true “totalitarianism” by differentiating between seemingly like things: Yes, both Kremlin propaganda and Madison Avenue advertising are, at some level, forms of brainwashing; but they are fundamentally different because . . . this was what the checklists aimed to answer.

It would be absurd to expect a list of criteria created for a specific time and place to apply universally for all time. In the Cold War, we were lucky enough to have an enemy who stood up and said, with no shame or dissembling, that they had only a single party in their elections because unnecessary competition was divisive and inefficient. It is easy to identify sham democracy in that case. It is not so easy when you have a phenomenon like today’s “uniparty,” where infinite immigration, endless foreign wars, and the ratchet of social liberalism go on regardless of which politicians the voters send to Washington.

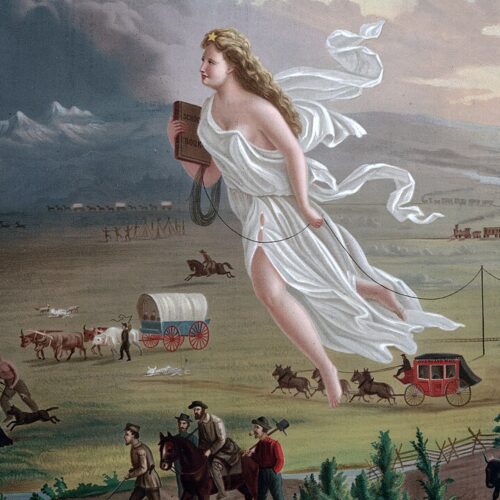

During the 20th century, the answer to who is oppressing you was almost always the state. Now power is distributed among various institutions, only some of which are officially part of the government. Sometimes businesses exercise power equivalent to that of the state. Sometimes the oppression lies in the absence of any central decisionmaker at all, which leaves power in the hands of a faceless blob—either the easily manipulated elite consensus known as “expertise,” or else the worst tyrant of all, the mob.

If you were outraged by school closures and classroom mask mandates during the Covid-19 pandemic, where could you go? To whom could you appeal? You would think that it would be your local school board, the logical place to turn if you have a problem with your local schools.

National Review writer Michael Brendan Dougherty did just that in January 2022, only to discover that the school board considered itself powerless to change its policies or even to moderate its most glaring absurdities, like the rule forcing Dougherty’s son and his fully vaccinated therapist to wear masks during speech therapy, a setting where it is important to see the other person’s mouth.

The school board passed responsibility to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The CDC then passed it right back, claiming to have offered only scientific guidance, not binding edicts. “Show me a school that I shut down and show me a factory that I shut down,” Dr. Anthony Fauci said in an interview in April 2023. “Never. I never did. I gave a public-health recommendation that echoed the CDC’s recommendation, and people made a decision based on that.”

“People made a decision”—other people. The locus of responsibility always lay somewhere else, further up or further down the chain.

The challenge in our modern form of totalitarianism is finding a human being who has authority, who is accountable, who can be persuaded, and who in the last resort can be removed and replaced. Modern liberalism has a deep hostility to individual authority. This hostility is both institutional and spiritual.

To start with the institutional: In short, everything is too big. Newspapers used to be local; now everyone gets their information from the same big national outlets and social media platforms. Banks used to be regional; deregulation allowed them to consolidate into a handful of behemoths. Small businesses have been replaced on America’s Main Streets by corporate chains. The man who manages your local hardware store is no longer an owner-proprietor but a functionary who answers to a head office in another city.

Big organizations are inevitably more bureaucratic. They lend themselves to opaque processes of decision-making where the really important calls are made behind closed doors by people whose names the public never learns. Social media censorship works like this. Tweets about the lab-leak theory of Covid’s origins or the ineffectiveness of masks were removed due to violations of Twitter’s nebulous “Terms of Service,” as interpreted by its trust and safety team.

These decisions are cloaked in faux objectivity by appeals to the discipline of “disinformation studies,” a bogus form of expertise that has been astroturfed throughout academia for the sole purpose of justifying censorship. “Disinformation” is a field with no intellectual content at all. Its credentialed experts, such as Nina Jankowicz, former executive director of the U.S. Disinformation Governance Board, are no more qualified to decide what information can and can’t be published online than any other American citizen.

Consolidation also makes it easier for small groups of people to force conformity on entire industries. Ownership has never been more concentrated in the history of American capitalism: The “Big Three” asset managers—Vanguard, State Street, and BlackRock—“are collectively the largest or second-largest shareholders in firms that comprise nearly 90 percent of total market capitalization in the U.S. economy,” according to John Coates of Harvard Law School. “This includes 98 percent of firms on the S&P 500 index, which tracks the largest American companies—with the Big Three owning an average of more than 20 percent of each company.”

These financial firms do not use their influence simply to make companies more efficient and profitable. They use their voting power to force companies to adopt left-wing environmental policies or diversity goals. If you have ever wondered why every big company in America seems to have the same incentive schemes for executives where bonuses are linked to meeting racial hiring benchmarks, it is because firms like State Street demand it. These demands are framed as appeals to best practices, not as mere expressions of preference—another way that expertise becomes a tool of gigantism.

In theory, consolidation could be favorable to strong individual leaders. The bigger the institution, the more a king-like leader could do with it. That is where the spiritual side comes in. The modern left quite simply hates individuality, independence, and self-possession.

In their essay “Totalitarianism, American Style,” Glenn Ellmers and Ted Richards cite a quotation from Winston Churchill: “Are not our affairs increasingly being settled by mass processes? Are not modern conditions at any rate throughout the English-speaking communities hostile to the development of outstanding personalities and to their influence upon events?”

Churchill, born in 1874, could remember a time before mass democracy, when institutions like the House of Lords and the limited franchise gave a role in public life to eccentrics, introverts, and curmudgeons, many of whom were surprisingly competent. He lived to see the 1960s when, not just in politics but also in culture, the aristocratic tastes of the few and the cruder tastes of the many were no longer able to coexist, as the latter crowded out the former.

The left’s antipathy to authority is motivated partly by an exaggerated fear of the dangers of bad authority—in other words, the average leftist’s inability to escape the psychology of “I hate you, dad”—but there is another reason, too. Individuality is viscerally offensive to leftists. Superiority demoralizes the mediocre; self-sufficiency leads too easily to defiance. The existence of an individual with the power to resist the pressures of conformity is a threat to the whole system and a maddening annoyance to those who prefer the rule of the masses. In Australia, it is called “Tall Poppy Syndrome”: stick your head up, get cut down.

“To the Bolshevik, there is something hideous and unseemly about the spectacle of anything so ‘chaotically vital,’ so ‘mystically organic’ as an individual with a soul, with personal tastes, with special talents,” Aldous Huxley wrote. “Individuals must be organized out of existence; the communist state requires, not men, but cogs and ratchets in the huge ‘collective mechanism.’”

Technology created this mentality, then and now. In the Communist era, it was industrial technology. Today it is digital. The online world runs on algorithms and data mining. Individual idiosyncrasies are overwhelmed by trends and patterns based on millions of users. The preferences of the masses are magnified. To go online is to be surrounded by them constantly without escape.

This digital world is also exceptionally vulnerable to manipulation. The man who is willing to stand up and defy conformity is rare in any age. When every social interaction is mediated by digital platforms, the pressure to conform is much greater and, worse, any person who does defy it can more easily be censored so his example does not spread.

The number of people willing to say that lockdowns were a bad policy, for example, was small, especially in the spring and summer of 2020. Among those with medical and public health credentials, it was minuscule. The number of Twitter accounts that had to be throttled in order to silence all dissent against lockdowns was therefore only in the dozens. Creating the illusion that lockdowns were universally approved was rather easy.

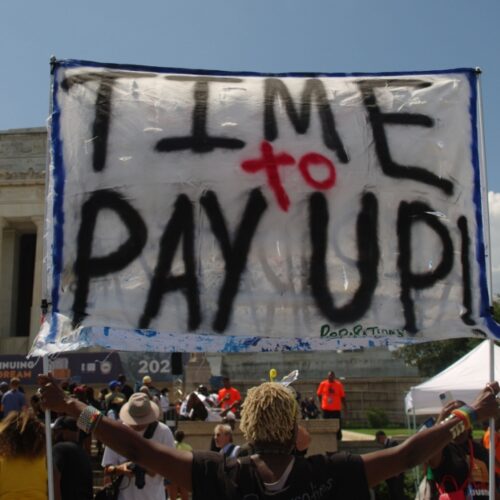

The left is correct that bad leadership is bad, but what they fail to understand—or perhaps, in some elite cases, understand all too well—is that no leadership means powerlessness and chaos. It does not matter how many people you have on your side. If you cannot coordinate, nothing will be achieved. A single flashpoint, a single leader to rally behind, can make the difference in bringing an end to tyranny.

This is why protests against lockdowns were prevented with such zeal. Facebook shut down anti-lockdown groups and event pages, some with tens of thousands of members, that wanted to organize rallies. These events had to be nipped in the bud before they began, because if those people knew how many of their fellow citizens agreed with them, they would be galvanized and the regime would be threatened.

In our modern totalitarianism, expertise amounts to “power without responsibility—the prerogative of the harlot through the ages.” Republican self-government depends on the possibility of debate. Citizens must be able to meet in argument face to face and offer perspectives, weigh tradeoffs, and hammer out compromises. One cannot debate an expert: he will appeal to authority and deny your standing to second-guess him. One cannot debate the mass: it has no face. These new tyrants are not only enemies to individuality. They make democracy impossible.

Helen Andrews is a senior editor at The American Conservative, and the author of BOOMERS: The Men and Women Who Promised Freedom and Delivered Disaster (Sentinel, January 2021). She has worked at the Washington Examiner and National Review, and as a think tank researcher at the Centre for Independent Studies in Sydney, Australia. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, The Wall Street Journal, First Things, The Claremont Review of Books, Hedgehog Review, and many others. You can follow her on Twitter at @herandrews.