Air Force Memo Reveals Racial Quota System

Editor’s Note: While the imposition of group outcome equality in universities and corporations has begun to spark outrage among the public, there is one institution that has been imposing quotas far longer and far more comprehensively than any other, but that has largely escaped criticism: the United States military. Will Thibeau, an Army Ranger veteran and director of the American Military Project at the Claremont Institute, takes a deep dive into the logic of the military’s group quota system, and ponders where that logic may lead the rest of the country.

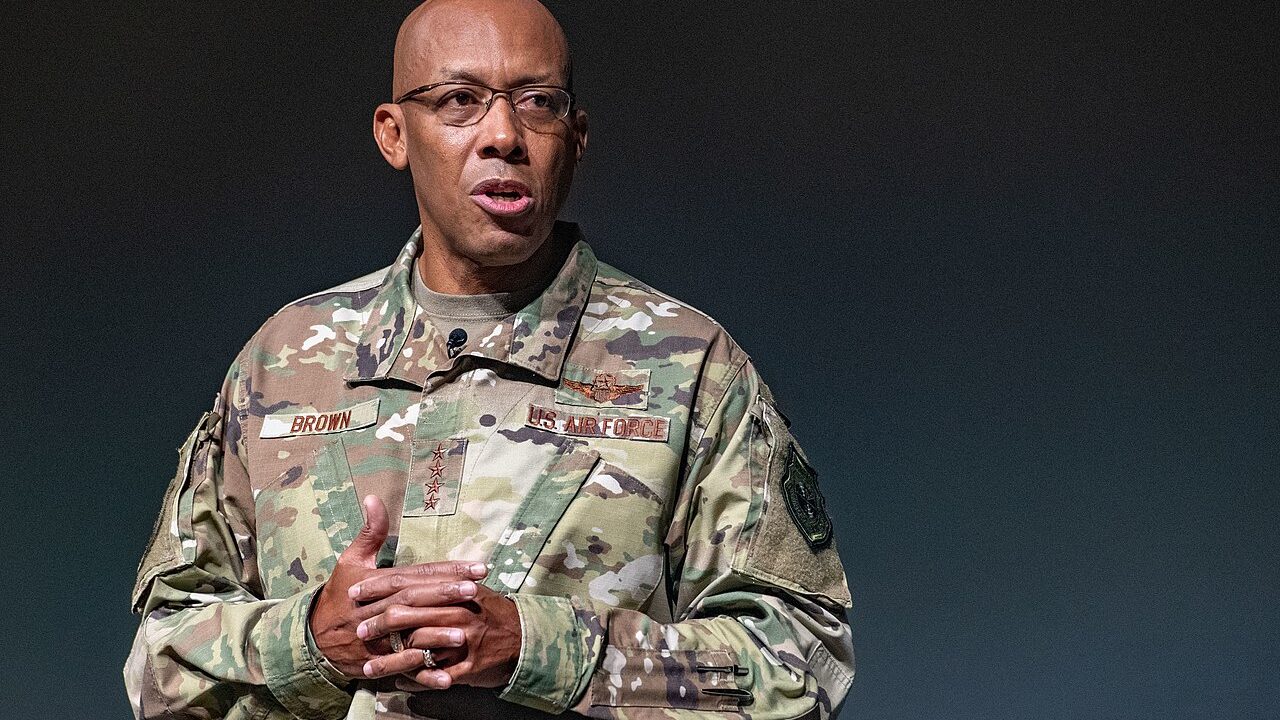

The American Military Project has uncovered an internal Air Force memo from 2022 in which General C.Q. Brown, now President Biden’s chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, directed the service “to develop a diversity and inclusion outreach plan aimed at achieving” set numerical quotas for the racial composition of officer applicant pools. This previously unreported memo is clear evidence that a group quota system is operating in the U.S. military, though Pentagon leadership are exceptionally careful to avoid using the term.

On July 26, 1948, President Harry S. Truman signed Executive Order 9981, establishing “that there shall be equality of treatment and opportunity for all persons in the armed services without regard to race, color, religion or national origin.”

In so doing, Truman explicitly called upon the spirit of the Founding. In a democratic nation for which the equality of man counted among the highest principles, to privilege one class arbitrarily over another could not be justified — certainly not in an institution whose character and fate were so entwined with that of the regime at large. This sentiment, of course, was born of long-standing national beliefs but brought to maturity by the course of history — namely, by the American experience in the Second World War. Black Americans had served ably and honorably throughout the conflict, and many had come home to less than a hero’s welcome. Integration — the old ethos of equal opportunity — was driven in large part by a sense of justice.

Yet the war had produced pragmatic lessons, too. The battle for Europe was waged on a scale and scope the likes of which the young American nation had not yet encountered. (Even our own bloody civil war, while presenting a graver political threat, amounted to a far less substantial military challenge compared against world war.) What’s more, the great powers of Europe were exhausted by war’s end, and with the rise of a serious rival in the East, it was more urgent than ever for America’s fighting forces to serve their singular purpose: to defeat the enemies of the United States in combat. Separate units, policies, and procedures for black soldiers had proved inefficient and ineffective, and the practice of segregation had stoked tensions both within American ranks and between America and her allies. The racial policy of the armed forces had proven an obstacle to the mission, and so it was cast aside. The effectiveness of the U.S. military was paramount, and the stakes were now too high. For a brief post-war period, the commitment to merit even led the Army to omit “Race” altogether as a category in personnel files.

It did not last long. Under the Kennedy administration and its secretary of Defense, Robert McNamara, the Truman-era desegregation order was radically reinterpreted. It was not enough, in the eyes of the new leadership and the context of the Civil Rights revolution, to ensure “equality of treatment and opportunity for all persons.” The military must now be a reflection of the nation, a goal that could only be secured through equal representation — which is to say equality of outcome. Beginning at West Point in the ‘60s, the Army established racial quotas in an effort to bring the demographic makeup of the officer corps in line with that of the nation, as University of Kansas professor Beth Bailey documents in An Army Afire. In 1967, an official directive came down from above that the academy “should have at least the same percentage of minority students as did the civilian college population,” regardless of how talent and qualification were actually distributed across the applicant pool.

Racial Quotas Today

Those quotas endure, though the activists and officers behind them go to great lengths to obscure their mere existence. A case in point is the testimony in January 2024 of Brigadier General (ret.) Ty Seidule before the House Government Oversight Subcommittee on National Security. For many years, Seidule was head of the history department at West Point; he is also a fellow at the liberal think tank New America and a member of the Department of Defense committee on changing names now deemed offensive, such as installations named after veterans who joined the Confederacy.

Seidule, aided by the committee’s Democratic members such as California’s Katie Porter, steadfastly insisted that the U.S. military does not operate on a system of group quotas. But Rep. Mike Waltz, a Florida Republican, showed Seidule West Point’s “Class Composition Goals,” marked with red numbers where the admissions committee did not meet the so-called goals for racial minorities or women in a given class. In the military, such red ink indicates a negative connotation that must be addressed before the next report. Seidule was unable to explain how this practice differs from a quota, other than semantically.

Congressional Democrats and the military brass may not be worried that Seidule was caught on the back foot; they can rely on the dutiful clips from Representative Porter’s questioning to advance the lie that the military does not use quotas to select and promote servicemembers. In the face of such concerted propaganda efforts, conservatives must, like Waltz, be just as committed to reminding the American public of the clear truth. Euphemisms aside, race and sex quotas have been defense policy since the time of Robert McNamara.

Even C.Q. Brown, President Biden’s new chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, has actively imposed racial quotas during his time in leadership. In August of 2022, Brown mandated that the Air Force define officer applicant pools based on race or sex. The common term “goals” — the same one employed at West Point — describes what any reasonable American would understand to be a quota. General Brown gave subordinate commanders barely two months to ensure their officer applicant pools reflected broader demographic reality, rather than being based on talent and qualifications.

Senator Eric Schmitt almost derailed General Brown’s nomination hearing in July, 2023 when he asked the (now-confirmed) Chairman of the Joint Chiefs about this race- and sex-based quota system. Democrat Senators Dick Durbin and Tammy Duckworth went to great lengths to run cover for Brown and his thinly veiled quota system. In the end, only eleven Republicans were even bothered enough to vote against Brown’s confirmation as the senior-most officer in all of the armed forces.

Time after time, senior military leaders make the existence of “goals” clear to Congress but act aghast when confronted about quotas. In another July 2023 hearing on the military service academies, Lieutenant General Steven Giland insisted, as if it should be the final word on the matter, “We have goals, sir, but not quotas.” This dodge is typical, yet no Republican member even bothered to ask LTG Giland how a policy that created an expectation of racial composition for each admissions class was different from a quota.

It is no mistake that the military’s lunge for nonsensical euphemisms mimics the language distortion overtaking other parts of our culture. As “comprehensive history” is to “critical race theory,” West Point’s “racial goals” are to race and sex-based quotas. The reality of the policy and practice is apparent to any sensible American, but the military’s effort to equivocate and confuse is as revealing as it is confounding.

Understanding the Army’s Case

This is more than just a squabble over terminology. In important ways, the military serves as the vanguard of the group quota regime. Quotas have an entrenched history in the armed forces, and it is not hard to draw a line from McNamara’s reforms to the establishment of outcome equality as the social ideal across every domain. As the woke agenda kicks into overdrive, and meets some resistance in academia and the private sector, conservatives must seize the moment and strike wokeness at the root: the group quota system that has existed in the military since 1968.

Democrats, establishment Republicans, and the Pentagon go to great lengths to insist that the very concept is a myth, that the military does not make personnel decisions informed by race- and sex-based quotas. This is technically true, in the sense that there is no written policy called “The U.S. Army Racial Quota.” But a raft of such policies exists behind a screen of euphemisms — “goals,” “targets,” “diversity,” all of which the brass claims to be merely “aspirational” — and these quotas do have a demonstrable determining effect on personnel decisions.

Recent evidence indicates the quotas are defining how the military recruits, selects, and promotes servicemembers. Internal Army data now indicates the percentage of white recruits has fallen by more than 10% in less than five years, as word spreads that the Army’s commitment to racial proportionality outweighs its historical focus on merit. Efforts to offset this decline with more “diverse” recruits have failed to sustain necessary force levels, as the historic base of military manpower has become an underrepresented group.

The Army justifies these policies with vague attestations to the importance of diversity in creating effective combat units. As the myth goes, the military must reflect the nation it defends to defend it well. In a telling congressional hearing in front of the House Armed Services Subcommittee on Military Personnel, no senior personnel officer of any branch was able to cite a research study or statistic that even alludes to the idea diversity makes for stronger infantry platoons or submarine crews.

When the Armed Forces are subtly, but radically, crafting personnel policy based on race and sex, rather than merit, the burden of proof is on the military to prove such change is in the best interest of military proficiency. Yet the case the Army has made is vague, misdirected, and easily debunked, as we will see. It is laid out in Chapter 2 of the Final Report of the Army Diversity Task Force, a document whose most ambitious claims have been undermined by the direction the force has taken since its release more than a decade ago. In that report, the task force acknowledges the significance of the postwar commitment to merit above all else, but argues: “While we are justifiably proud of the diversity we have achieved through equal opportunity and equal employment opportunity, our focus on the future must go beyond these efforts.” That is: “equality of treatment and opportunity” is not enough.

In providing context for its arguments for outcome equality over equality of treatment, the task force claims: “Many of the current practices that drive successful diversity initiatives originate from the need to continuously improve business outcomes and better perform the organizational mission.” As this assertion suggests, the whole case boils down to corporate jargon — a fact that betrays two crucial errors. First, it assumes that the “diversity initiatives” sweeping across corporate America have, in fact, “improve[d] business outcomes,” which is to say that diversity, equity and inclusion (DEI) radicalism has borne good fruits. Second, it assumes such initiatives can be applied whole cloth in the military — that is, that the armed forces are not meaningfully different in character than any random corporation.

Common sense and a clear intellectual tradition align against this reading. As Samuel P. Huntington explained in his 1957 book, The Soldier and the State, the military must be based on ideals separate from the politics and ideologies prevalent in society to maintain military competence. The military is unique in its relation to society — especially a liberal society foreign to the rigor and discipline of militarism.

Reading the report of the Diversity Task Force, one gets the sense that the group quota partisans understand this, in their way. Among the seven “significant considerations” listed in Chapter 2 is “National Implications,” in which the task force looks forward to “new opportunities to influence diverse communities” — a substantial departure from the purely representative mission they claim at the outset. Under the label of “Global Engagement,” the logic is extended dramatically:

The anticipated nature of future global engagements calls for a diverse Army prepared for the human dimension of conflict. Due to current and future security environments, there is a need for a culturally astute and adaptive Army, capable of responding to American interests within any environment. A highly successful, long-term organizational diversity effort will give the Army an opportunity to become a national leader in diversity. Accomplishing this task will make a powerful statement to our workforce and the Nation. Success in understanding our internal cultural and other differences will create a predisposition for respecting differences that extends to preparation for global operations. Developing an appreciation for foreign cultures before appreciating our own cultures is inherently difficult. However, our internal success will enhance our ability to go beyond our own differences, and become more receptive to cultures of others with whom we may interact.

At least on some level, the defense establishment’s new racial posture is outward-facing in purpose. The group quota activists who have spent years remaking the U.S. military according to the logic of “representation” expect their reforms to have massive downstream effects.

Of course, none of this can be achieved without first implanting woke ideology within the armed forces. And so, with the euphemistic title of “Education and Training,” the task force hopes that “the Army’s future demographics will bring new language and cultural challenges within our own ranks.” The expectation of the diversity brass is that rank and file servicemembers will be conditioned into a new way of thinking about and engaging with the world. As the task force puts it, “cultural understanding begins at home.”This reeducation effort was recently illustrated starkly in public remarks delivered by Lt. Col. Bree Fram, a Space Force officer who identifies as transgender. Fram dismissed the standards of “dignity and respect” as insufficient, insisting instead that servicemembers must be compelled to “intentional inclusivity” — including adopting “symbols of Pride,” imposing transgender pronoun use, and “initiat[ing] difficult conversations about racial and gender barriers.” As in the foundational task force report, Fram claimed that “we know” such efforts “make us stronger.”

Along those lines, the other four prongs of the Army’s case for quotas — “goals” — are all related to manpower: accessions, retention, performance, and personnel processes. The underlying idea is that recruiting strategy must be reconciled to the facts of demographic change, and that (once a more diverse force is created from above) an appreciation of diversity will strengthen esprit de corps and feed into better outcomes. Ironically, this argument for diversity hinges on a kind of race essentialism: Why, as the report’s logic suggests, do black soldiers need to be led by black officers? This is half a step away from the logic of segregation, and another clear departure from the tradition of equality and merit in our armed forces.

Beside this philosophical problem, the claim that these efforts strengthen our forces is flatly refuted by the situation on the ground; both recruiting and retention are in a crisis the likes of which our military has never seen before. By the end of 2023, the Army had dropped to its lowest full-time manpower level since before the Second World War, after missing its annual recruiting target by roughly 15,000. The other services logged similar shortfalls and similar declines. This failure has been driven in large part by a steep dropoff of the military’s historical core, including families with a long tradition of service. As the Wall Street Journal reported in June 2023, 80% of soldiers have typically come from such families, yet many veterans are now actively discouraging their children and other young relatives from enlisting. The result is an Army that is not just more diverse but demonstrably weaker than it was in previous generations.

Where We Go From Here

In 2024 America, the logic of the woke regime — what we call the “group quota regime — is clearly the most pressing of the ideologies whose encroachment on the military Huntington warned against. For some time now, the military has used race and sex as a demographic goal for subordinate units and organizations. As the Army’s own guiding documents show, this policy is part of an intentional social agenda, and it has been carried out regardless of the hollowness of its practical promises.

Beyond the splashy headlines of wokeness in uniform — bizarre revelations of drag shows on aircraft carriers, or the brazen Pentagon Pride events — the military quietly maintains a group quota regime that would make even Ivy League admissions officers blush. While elite universities may outpace the armed forces in practice, none has been shown to operate on a quota system as direct and undeniable as that now demonstrated by the Air Force memo. Though shrouded in euphemisms, policies like Gen. Brown’s make the race and sex demographics of an organization a central principle of Pentagon decision makers, undercutting both the ethos and the capabilities that keep a fighting force alive.

Republicans in Congress have not done anything to fix this. The 2023 NDAA touted by some as “conservative” included not a single provision that would disrupt the military’s quota-based affirmative action regime. Democrats allowed provisions like pay caps on DEI roles and tepid reaffirmations of merit and standards to remain in the NDAA, because they know the entire Pentagon infrastructure is organized around “diversity.” A few tweaks here and there will not meaningfully undermine their efforts. The 2024 election cycle may be the last chance for Republicans to show they understand the problem.

At this point, it is no longer a question of whether quota-based policies might affect readiness. There is clear evidence that’s already happened. The nature of the crisis is now hardly in dispute. What is needed now is a genuine confrontation with the decay of standards in the military — beginning with a bold effort to dismantle a system of affirmative action more extreme than is to be found at any American university. The Left will hold out to the political end to preserve this system, but that fact only underscores the urgency of the fight over merit in the one institution where it decides life and death.

Will Thibeau is an Army Ranger veteran and director of the American Military Project at The Claremont Institute.