Censorship in the New Regime Is Corporate

Editor’s Note: The first step in winning a war is to recognize the fact that you are in one. This means, first and foremost, to come to know your enemy and his goals. In a recent essay for this site, Glenn Ellmers and Ted Richards of the Claremont Institute make a compelling case that the present enemy—the “woke” or group quota regime—is a totalitarian threat, and that its aims are nothing short of revolutionary. While our own troubles may seem far removed from the hard totalitarianism of the twentieth century, Ellmers and Richards argue that the six traditionally accepted elements of totalitarianism are already present in woke America. What’s more, they identify three factors that are unique to the tyranny of the present day.

Sohrab Ahmari was the op-ed editor of the New York Post when the paper’s groundbreaking reporting on Hunter Biden was suppressed by Big Tech in the middle of an election. Here, Ahmari reflects on the now-infamous episode and draws out its most startling implication: That information control in the new regime has been handed over to a handful of corporate powers, and that even right-wing critics are not ready to make the kind of sweeping reforms required to break the grip of the new totalitarianism. This is the third in a series of nine contributions by leading experts on the nine defining elements of what Ellmers and Richards dub “Totalitarianism, American Style.”

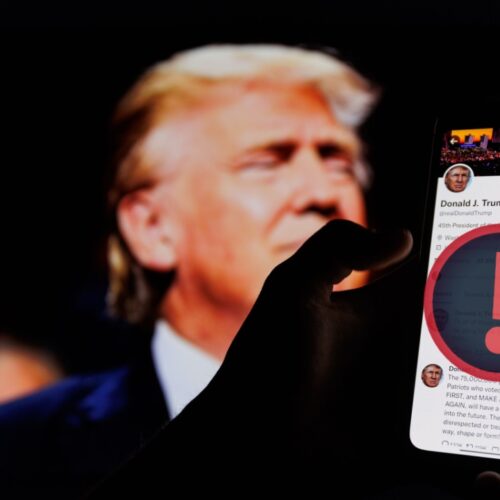

October 14, 2020. It’s one of the dates etched in my mind, alongside my wedding anniversary, my kids’ birthdays, and my reception into the Catholic Church. Unlike those happy occasions, however, October 14 is associated with a dark memory. It was the day the New York Post, where I was the op-ed editor at the time, published the first exposé on Hunter Biden’s laptop — and was censored by Facebook and Twitter and had its official account suspended on the latter platform.

Here is the opening paragraph of an October 15 column that may well have constituted the paper’s first intervention in response to the censorship it suffered: “This is what totalitarianism looks like in our century: not men in darkened cells driving screws under the fingernails of dissidents, but Silicon Valley dweebs removing from vast swaths of the Internet a damaging exposé on their preferred presidential candidate.”

I can still feel the genuine dread that inspired these words. The 35-year-old me that penned them would have agreed with Glenn Elmers and Ted Richards when they argue that the United States has entered a phase of soft despotism, even soft totalitarianism, at least with respect to the media. And I still agree with that assessment. What’s changed, or perhaps deepened, is my understanding of the precise nature of this despotism, and what it would take to overcome it.

The fundamental problem is the enormous concentration of media and technological prowess in a relatively few oligarchic hands. These media and tech overlords and their managerial servants, as we now know, are all too willing to collude with the state apparatus to censor inconvenient truths. But I fear that by focusing primarily or even solely on such collusion, opponents increasingly ignore the bedeviling privatized quality of the current tyranny.

Put another way: The censorship of the Post would have been inexcusable even if there had been no coordination between social media and the feds. Nor should we rest content that at least one important platform, Twitter, is now controlled by Elon Musk, an oligarch perceived as friendly to the right. For that in no way alleviates the threat to self-government posed by concentrations of private power as such. If anything, it risks lulling us into abandoning more systematic reforms.

My October 14 had started normally enough. “What a scoop!” I thought to myself when I woke up and first opened my Post app to see what my news-side colleagues had been up to. Normally, I would have looked up the day’s cover—“the wood,” in tabloid parlance—in the paper’s pagination system the night before. But in this case, I hadn’t bothered for some reason, and got to read it at the same time as everyone else.

The Post’s first Hunter piece concerned the illustrious presidential son’s business dealings in Ukraine. E-mails recovered from the laptop suggested that Hunter in 2015 had set up an encounter between executives from Burisma, the shady Ukrainian energy firm that was paying him at least $83,000 a month to serve on its board, and his father, then the vice president of the United States and the Obama administration’s point man on Ukraine.

I wasn’t alone in my excitement. As the morning went by, the story garnered massive attention on social media—until suddenly, it disappeared. At about 11 o’clock Eastern, I spotted a curious online statement from a communications staffer at Facebook named Andy Stone (previous gigs listed in his online bio: the Democratic Congressional Campaign Committee and the office of Sen. Barbara Boxer, Democrat of California). Stone’s statement read: “I want be [sic] clear that this story is eligible to be fact-checked by Facebook’s third-party fact-checking partners. In the meantime, we are reducing its distribution on our platform.”

Third-party fact-checking? Huh? Over the previous four years, mainstream outlets had published a mountain of anti-Trump stories that turned out to be so much bunkum. Remember McClatchy’s claim about Trump lawyer Michael Cohen supposedly rendezvousing with his Russian handlers in Prague? Or Buzzfeed’s story about Trump suborning Cohen to commit perjury before Congress? Or when CNN reported that James Comey was about to dispute in congressional testimony Trump’s claim that the FBI director had reassured the president he wasn’t under investigation? Or The Guardian newspaper’s claim about Trump campaign chief Paul Manafort and WikiLeaks founder Julian Assange meeting at the Ecuadorian embassy in London? Remember the Steele Dossier, with its lurid claims about Moscow pee-pee tapes?

Most of those stories rested on the dubious pronouncements of unnamed sources. Yet they were permitted wide circulation even after they were revealed to be factitious. By contrast, Andy Stone and his colleagues had deemed fit to use their algorithmic wizardry to reduce circulation on the Post’s Hunter reporting pending third-party “fact-checking.” This, even though the Hunter Files rested not on anonymous sources, but a hard drive and screen captures of e-mails.

Twitter went further. The platform outright banned the story from being shared, including in private messages between users, and suspended the Post’s account. All this, on the grounds that the paper had supposedly violated Twitter’s “hacked-materials policy.” High-level Twitter executives considered that excuse to be risible at the time, as we now know thanks to Musk’s disclosures of internal deliberations at the firm. Yet in those early days, Twitter refused to budge from its initial determination; the Post, America’s oldest continuously published daily, founded more than two centuries earlier by Alexander Hamilton, remained suspended for a fortnight.

On October 15, the same day my “totalitarianism” column appeared, the paper published a second laptop exposé, this one concerning Hunter’s dealings with a Chinese Communist Party-linked firm. That story, too, was banned on Twitter, including from being shared in direct messages. This, even though Tucker Carlson soon corroborated its details via one of Hunter’s partners, a former naval officer and Democratic Party supporter named Tony Bobulinski. Twitter’s second act of censorship was all but forgotten in the days and weeks to come, even by congressional Republicans who skewered then-Twitter boss Jack Dorsey over the suppression of the Ukraine material.

Meanwhile, the traditional corporate media circled the wagons around the tech firms. Most notably, Politico broke the news that some 50 former top intelligence officials had signed a statement warning that the laptop story bore the hallmarks of a “Russian information operation.” In doing so, the outlet made no effort to interrogate or corroborate the claims of the ex-spooks. The Gospel of John Brennan needed no critical examination—an abject posture toward the Intelligence Community that recalled the worst of the media’s post-9/11 errors.

The mainstream message—read off in unison, as if all of these outlets had received the same memo—was that the Hunter Files were “disinformation,” possibly planted by the Kremlin, and certainly not worthy of looking into. CNN published a piece headlined “The Anatomy of the New York Post’s Dubious Hunter Biden Story,” in which a reporter for the network celebrated the fact that “the media world has largely ignored the Post’s Hunter Biden story.” Another CNN piece claimed that “this is a classic example of the right-wing media machine.” Really? How did CNN know that? Had the cable-news outlet done any more-than-cursory, original reporting to prove or disprove the Post’s claims?

The very few reporters who dared press Joe Biden about his son’s foreign shenanigans, meanwhile, came under severe attack—not just by the candidate, but by their own colleagues. Bo Erickson of CBS took enormous heat for gently asking Biden to comment. Greg Sargent of The Washington Post reproached Erickson on Twitter: “The real problem here is this is a useless question from a journalistic perspective. It won’t inform people or hold Biden accountable in any meaningful way. Large parts of the story are invented/unconfirmed/highly dubious. What is learned by placing the work of denying them on Biden?”

The taxpayer-funded National Public Radio outdid all other outlets for sheer incuriosity. Asked why NPR hadn’t touched the Hunter Files, news editor Terence Samuel answered: “We don’t want to waste our time on stories that are not really stories, and we don’t want to waste the listeners’ and readers’ time on stories that are just pure distractions. And quite frankly, that’s where we ended up, this was … a politically driven event, and we decided to treat it that way.”

Many of these outlets would later pull an about-face, devoting the resources needed to do their own investigation into Hunter Biden and finding that—surprise—the Post had gotten the story right, down to the small details. But by then, the social media censorship, legitimated by the corporate media, had achieved its purpose; Joe Biden was safely installed in the Oval Office.

In the wake of the Hunter censorship episode, Republicans briefly seemed to embrace reforms that would go to the heart of the problem: the fact that our digital public square is controlled by a handful of private tech firms wielding an all but limitless power to determine the parameters of permissible speech. The Hunter Files, along with the censorship of pandemic dissidents, cast a cold light on the ability of Big Tech to use its market power to achieve what the midcentury economist John Kenneth Galbraith called “conditioned power”: the power to shape what millions of people get to say, know, and think.

Systematic reforms aimed at curbing this combination of compensatory and conditioned power were on the table. Foremost was reforming or overturning Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act, the well intentioned but outdated Clinton-era law that allows social media platforms to censor content—that is, to act like traditional publishers—without bearing any of a traditional publisher’s liabilities.

Then, too, no less a figure than Supreme Court Justice Clarence Thomas floated the idea of treating social media platforms like common carriers. The ancient common law principle holds that providers of mass services like toll bridges, say, cannot unreasonably discriminate against users. Applying it to Big Tech would have offered a solution to the problem that was elegantly in keeping with the Anglo-American legal tradition.

Last but not least, there was a great deal of antitrust talk. Even laissez-faire ideology, after all, permits breaking up firms that unduly monopolize their respective markets. That’s certainly true of Big Tech firms, especially in their dealings with much weaker traditional outlets (like the Post). As antitrust experts like Lina Khan, President Biden’s competition czar, have documented, firms like Twitter and Facebook sit on both sides of digital-advertising and content transactions, hindering competition to an obscene degree.

As advertising platforms, Big Tech companies force news outlets to compete with them on their own territory, even as they also attract eyeballs and subscribers away from the outlets that put capital and sweat equity into producing original journalism. And those subjugated, the traditional outlets, dare not fight back lest they lose still more ground. Rather, each outlet tries individually to do the best it can, given this structural asymmetry, with varying degrees of success. Many simply fail.

All this, as I say, was once on the table. But then Elon Musk took over Twitter, and suddenly the conversation shifted. Not long after his purchase, Musk disclosed the Twitter Files—a cache of the firm’s internal censorship deliberations during COVID and the Hunter episode showcasing close coordination between Twitter and federal authorities and/or the Biden campaign when it came to policing controversial content. The revelations were indeed shocking, and raised serious constitutional issues: If Twitter under Dorsey had acted as a surrogate for the government, then its censorship may well have implicated the First Amendment. The firm could not hide behind private action. Soon, however, this element of state-corporate collusion became the overriding priority of all Big Tech reform efforts on the right.

Forgotten, for the most part, were the deeper concerns about concentrated power, Section 230 abuse, and the privatized public square. It helped that Musk seemed to relish engaging with and even promoting Twitter accounts associated with the so-called dissident right. Many conservatives came to conclude that “one of our own” was running Twitter. But Musk’s interests as an oligarch are not identical with those of populists and national conservatives. He has his own material interests. These happen to coincide with those of elements of the online right today, but they could shift tomorrow; when there’s two-hundred billion bucks at stake, people tend to be ideologically flexible.

More to the point, the problem of arbitrary and unaccountable privatized censorship hasn’t gone away. There continues to be plenty of censorship under the Musk regime, after all, including the use of algorithmic tweaking to promote the kinds of content Musk personally prefers (hint: it’s not essays critical of Big Tech like this one, but sensational videos and memes).

To be at the mercy of a friendly oligarch is still to be at the mercy of an oligarch. It doesn’t mean we have overcome the danger posed by concentrations of private economic power to self-rule and authentic freedom.

Sohrab Ahmari is a founder and editor of Compact and the author, most recently, of Tyranny Inc.: How Private Power Crushed American Liberty—and What To Do About It.